Transmission

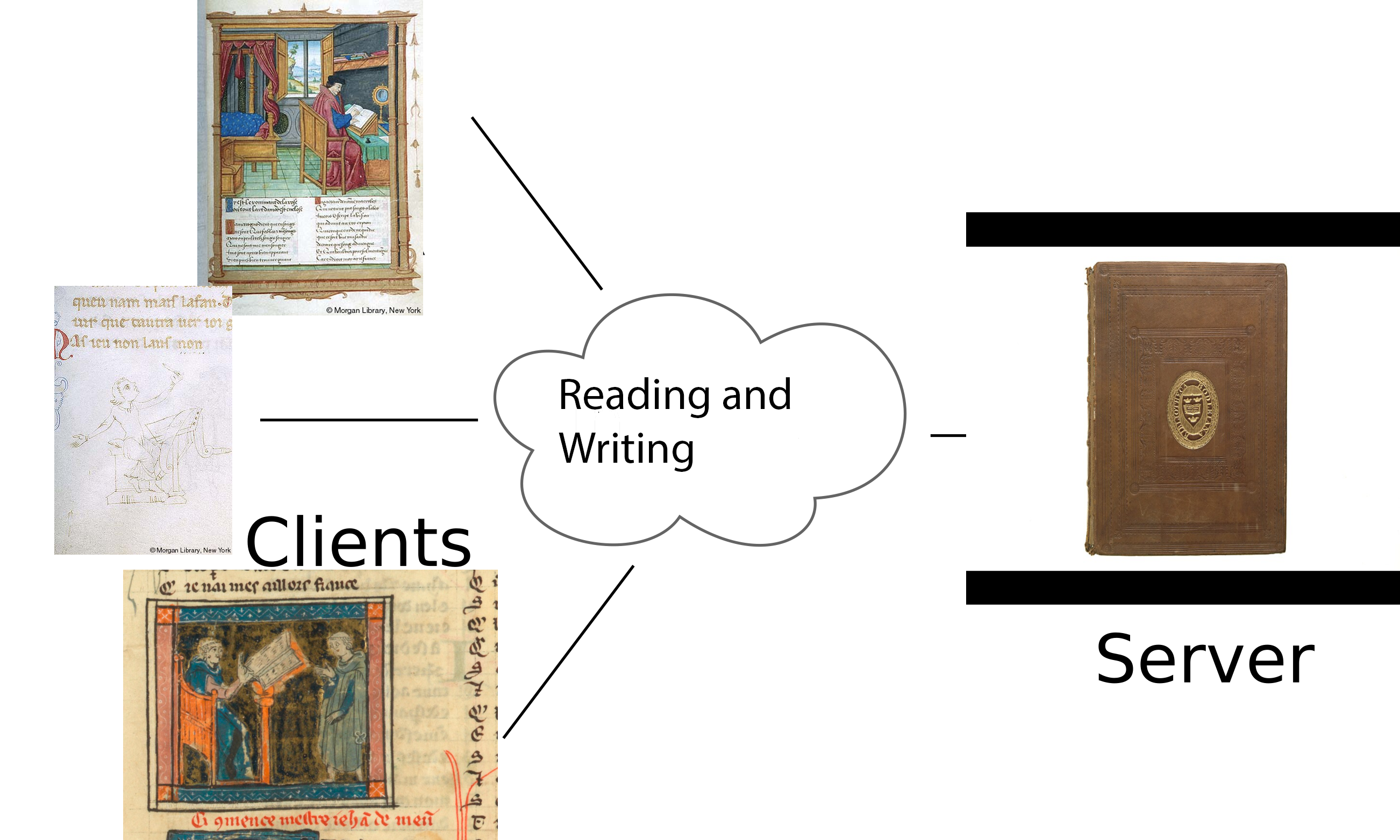

(Original image from Wikimedia Commons, edited version uses images from Pierpont Morgan Library MS 819 and 948, Dartmouth Rauner Codex MS 3206, and Bodleian MS. D'Orville 301)

If a medieval person wanted access to a particular work, there were a few typical paths they could take. They could go to a manuscript containing the work, have the manuscript brought to them, or they could arrange for a copy of the text in a given manuscript to be made for them. These copies would typically be created on-demand, copies were typically not created before they were called for like they are nowadays for printed books. The shape and size of the work often determined which of these paths would be taken. Shorter works could be memorized or quickly transcribed, whereas longer works, or those with intricate images, had to travel or be traveled to: "One copy sufficed in these cases, so long as it was conveniently located"1.

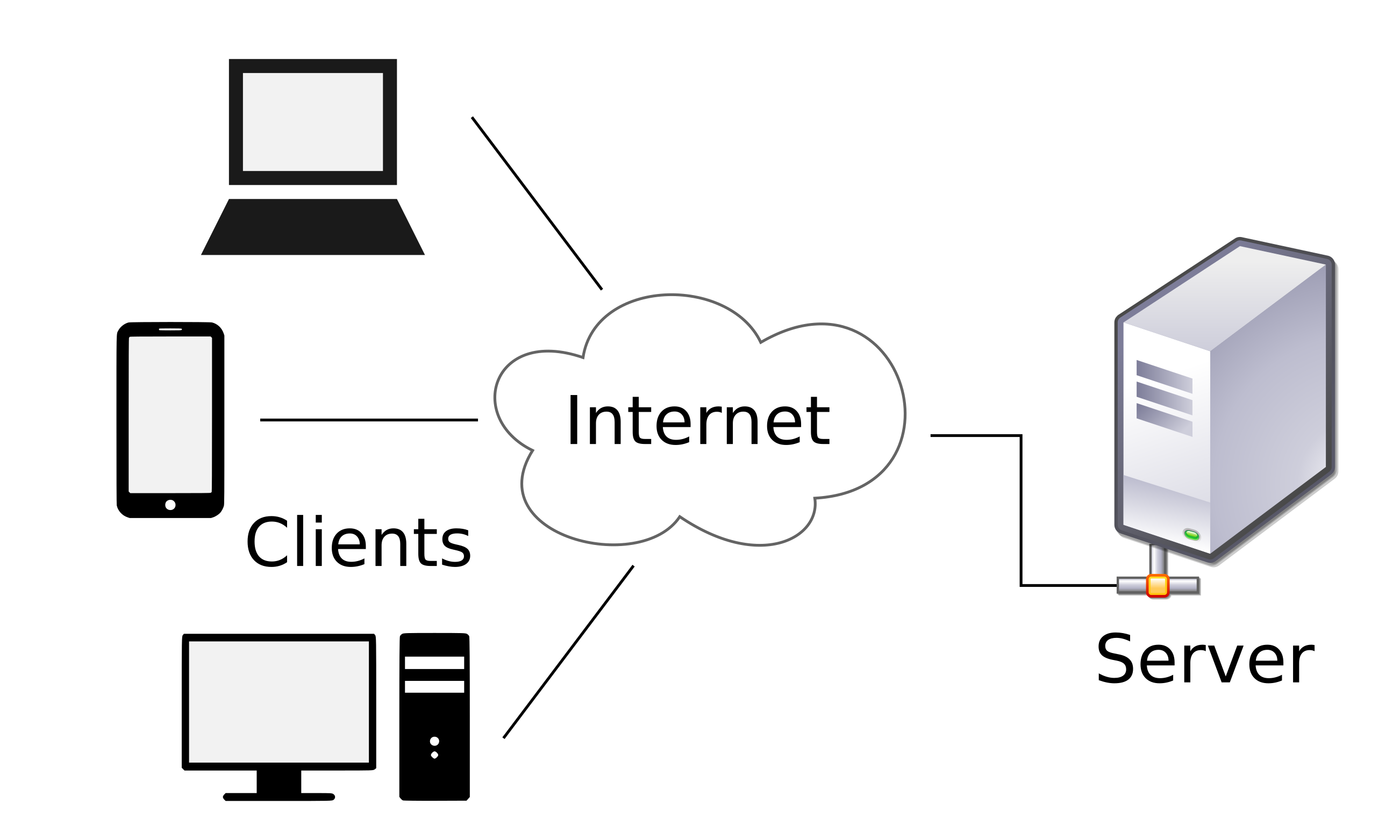

On the Internet, copying combines elements of these paths for a familiar experience. Files are often located with a sufficient singular copy on a server exposed to the Internet, and people ('clients') who wanted access to the file typically send a request across the Internet to the server, at which point the server transmits a copy of the requested work back across the Internet to the client (loosely depicted in the first image above).

Footnotes:

Bourgain 140-141