Use

When I interact with a modern book, I typically read it alone, silently in either a library or my apartment. Medieval people did not always interact with texts in the same way we typically do today. Part of the reason for this is due to the literacy of the populations. Though a larger portion of the population was not literate (as we understand it today), they were not cut off from the works that have come down to us in written form: texts were made accessible to a larger population through performance, as many (especially literary) texts were read aloud1. Many texts were born of an oral tradition, only being written down after they had been created and circulated2. Because works of literature were not determined by their transcribed forms, their structures were in part determined by the rhythms of voiced language, and there was space for improvisation and rewriting3. The role of a text in Medieval societies was not limited to the quiet reading rooms we know today.

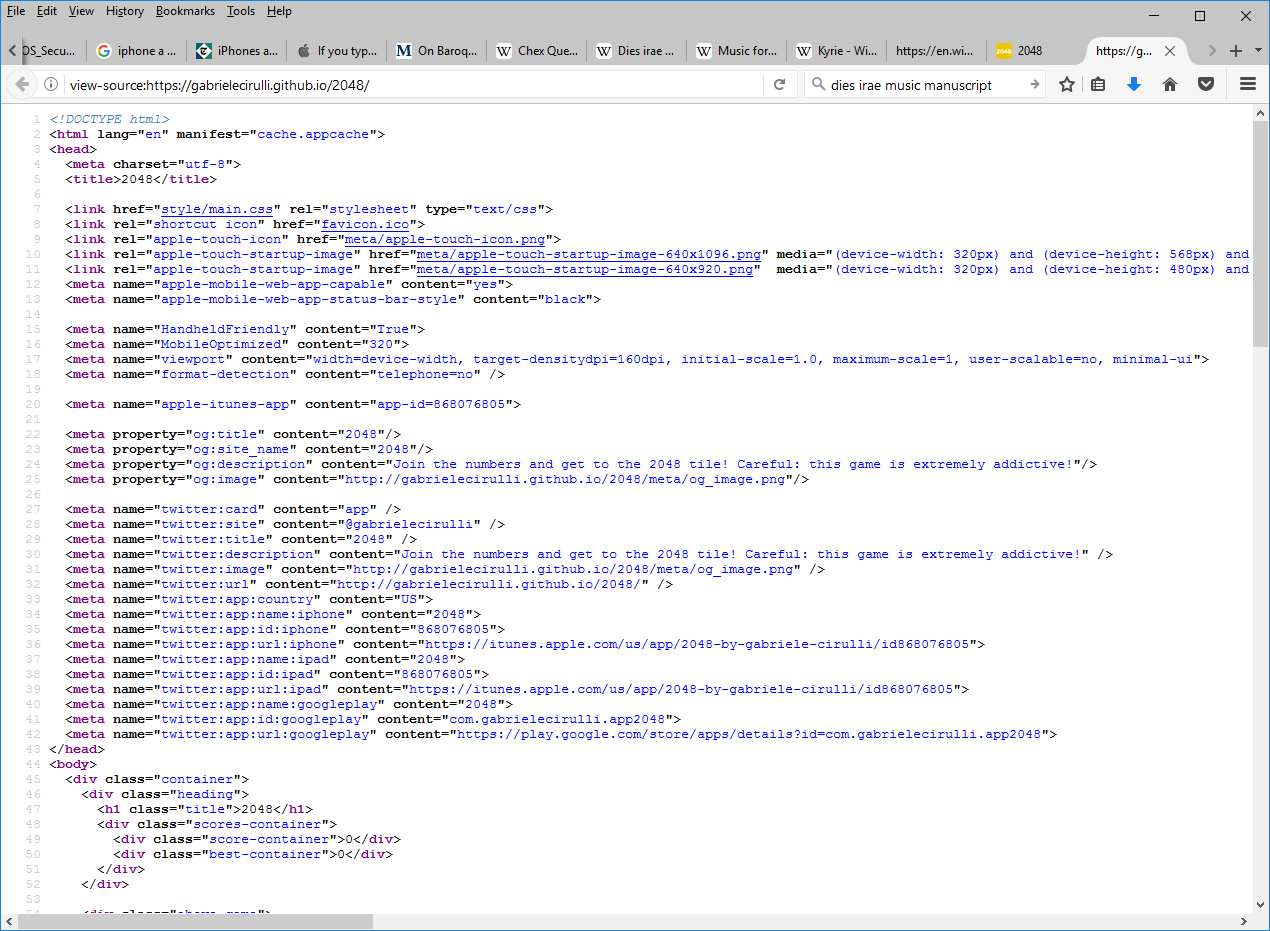

As the Medieval experiencer might interact with a work by having it read or acted out by someone else, a modern experiencer of software only very rarely interacts directly with the digital artifact. Here, the artifacts are executables, files containing some sort of code. Often this code has been transformed (compiled) into a "machine-readable" format (especially in the case of proprietary software), but frequently (for example, on the World Wide Web or for certain computer programming languages such as Python, Ruby, Perl and many others) the code is left as it was typed by a (typically) human programmer. The primary and intended mode for interacting with software is by running it, by taking the file containing the code, and processing it to produce some sort of effect. The raw content of an executable, whether they are machine-readable or programmer-readable, is not legible to most of the (human) population, as its form is only related to its intended form in subtle ways that are often incredibly difficult for a human to decipher.

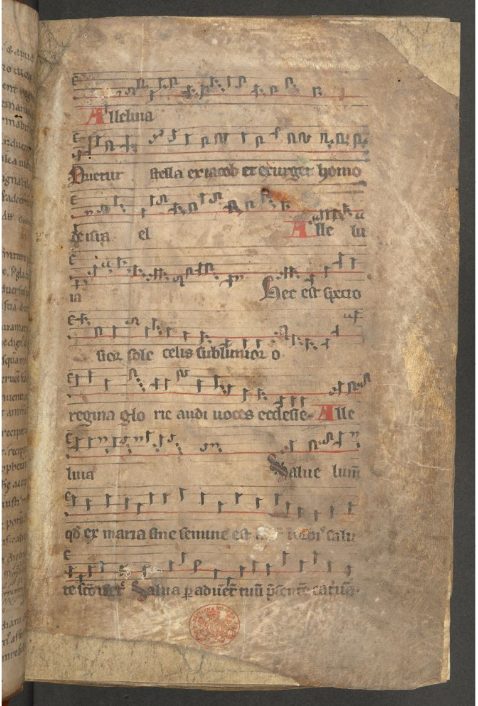

The two images selected here show that the 'raw' forms of manuscripts and (here) webpages are significantly disconnected from the forms of the works intended for an experiencer. On one hand, we have a page of sheet music from folio 2r in Add MS 18031 in the British Library. As music, as a chant, this work is not meant to be read silently, it is meant to be chanted. On the other, we have a portion of the source code to a game called 2048 4. This is far from the form intended for someone to interact with, and the 'reader', here a web browser, mediates the experience in a way similar to how a group of actors or someone reciting a work might.